Artificial Nature and Natural Artifice

Philippe Codognet

Professor of Computer Science

Université de Paris 6

LIP6, case 169,

4, Place Jussieu, 75005 PARIS,

France

Philippe.Codognet@lip6.fr

The title of this paper is borrowed from Claudio Tolomei, a sixteenth century Italian humanist from Siena, who used these words to describe the Manierist gardens where natural vegetation was intermixed with human constructions and technological devices : not interactive waterworks but also statues, grottos and “follies”, as for instance in the Orsini garden at Bomarzo[1]. This time was the heyday of the « double oxymoron », linguistic mirror of the stylistic boldness of the manierist painters[2]. Oxymoron that is today revived in the contemporary buzzword : « Virtual reality ».

Virtual

Reality (VR) is currently coming out of the research labs to reach mainstream

audience. After moving from the textual computer to the flatland monitor in the

previous decade, the 90’s has seen the emergence of Virtual Reality as the next

technological frontier. Sooner or later all computer interactions will be in

three dimensions, even if always through the classical Albertian window[3]

of the screen rather than with complex visual or haptic devices. The World Wide

Web will also be affected by this revolution, and we will soon change our way

of browsing the Internet from surfing flat HTML pages to diving into 3D virtual

worlds, that is, virtual spaces where digital communities could meet and

experiment new communication media.

I. Virtual Artworks

Some

experiments have been already done with VR immersive art installations. These

works has been in general realised with new technologies such as CAVE

environments[4]

(created by the EVL group at the University of Illinois in 1991) or Head

Mounted Displays (HMD for short, created at NASA in1984), following the

original ideas of Ivan Sutherland (1968) and the forgotten pioneering work by

Morton Heiling (1960).

Several artworks based on VR technologies have been created in the late nineties, among which the most well-known works are :

- “Perceptual

Arena” by Ulrike Gabriel, Cannon ARTLAB, Tokyo, 1993

-

“reConfiguring the CAVE” by Jeffrey Shaw, Agnes Hegedüs and Bernd Lindermann,

ICC (Inter Communication Center), Tokyo, 1997

- “Osmose” (1995) and “Ephemere” (1998) by Char Davies

- “Icare” by Ivan Chabaneau, CICV (Centre International de Creation Video), Montbeliart, France, 1997

-

“World Skin” by Maurice

Benayoun, Ars Electronica Center, Linz 1998

-

“Traces” by Simon Penny, Ars

Electronica Center, Linz, 1999

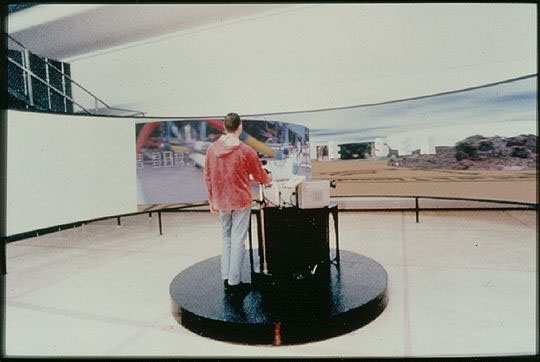

Close to these apparatuses are the use of circular projection walls surrounding the spectator and creating an interactive virtual environment, exemplified in Jeffrey Shaw’s “Space - a user’s manual” (1995), a richer version of his famous “Legible City” (1988-1991), and Agnes Hegedüs’s “Memory Theatre” (ZKM, Karlsruhe, Germany,1997). These devices are indeed downsized versions of Jeffrey Shaw’s earlier project EVE (Expanded Virtual Environment), initiated in 1993, which is a large semi-spherical projection dome on which video are projected, following the spectator head tracking.

A

cheaper version of virtuality is feasible within the flat monitors of standard

computers : 3D worlds rendered with the VRML description language (Virtual

Reality Modeling Language) and displayed with an adequate browser. This medium

has already been used in some artworks such as “suspension” by Jordan Crandall and

Marek Walczak (Documenta X, Kassel, Germany, 1997) or the Web version of

“Icare” by Chabaneau (also online in 1997).

Ulricke Gabriel Perceptual Arena, 1993

Maurice Benayoun, World Skin, 1998

Jeffrey

Shaw, Space - a user’s manual, 1995

In

a scientific context, VRML technology has been used for creating modern Wunderkamern (curiosity cabinets) and

representing, as in the Renaissance, the microcosm and the macrocom[5], that is

the depiction of the human body (and its inside) and the cosmos, see for

instance the 3D reconstruction of the Mars landscape by NASA and SGI from

pictures taken by the Mars Explorer.

One

should nevertheless distinguish between the two apparatuses mentioned at the

beginning of this talk, the CAVE and the HMD, as they seem to be used for

different purposes in artworks. CAVE or CAVE-like environments are used to

represent virtual (but Euclidean) spaces (e.g. Space - a user’s manual by

Jeffrey Shaw), whereas works using HMD are more oriented towards abstraction

(e.g. Ulrike Gabriel’s perceptual arena).

Is there here a dichotomy

between a perspectivist outside space and an inner abstract self ?

II. The prehistory of Virtual Reality

Let us now rewind Time and investigate the historical background of these apparatuses, in particular the Renaissance.

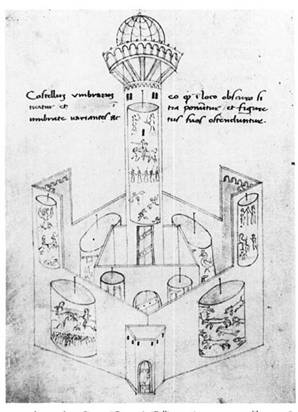

First

of all, the castellum umbrarum ,

castle of shadows, designed by the venetian engineer Giovanni Fontana in his

manuscript (bellicorum instrumentum

liber, 1420[6]),

which can be best described as a Pre-CAVE installation. This is a precise

description and depiction of a room with walls made of folded translucent

parchments lighted from behind, creating therefore an environment of moving

images. Fontana also designed some kind of magic lantern to project on walls

life-size images of devils or beasts. The use of projected images on walls was

later developed by one of the major figure of baroque humanism, the Jesuit

father Athanasius Kircher, « master of a thousand arts », in his book

Ars magna luce et umbrae (1646).

|

|

|

Giovanni Fontana, Bellicorum instrumentum liber, 1420

The

second historical background of virtual environments can be found in trompe l’œil frescoes in Venetian,

Florentine or Roman villas in the Renaissance : for instance the

”Perspective Room” by Baldassare Peruzzi in the Villa Farnesina (Roma, 1510),

the “Giants Room” by Giulio Romano in the Palazzo Te (Mantua, 1530-32) or the

frescoes of the Villa Barbaro by Paolo Veronese (near Treviso, 1561). In the

Perspective Room, false windows open on a fictitious painted landscape, as an

acme of perspectivist and illusionist virtuosity. Leonardo himself also worked

on such pictorial schemes[7]

and one of his codex contains a drawing describing how to illusionary project a

painting on a cubic volume in order to recreate a non-distorted image, a device

put at use much later in an electronic manner by the conceptors of the CAVE immersive 3D environment at the University of Illinois[8]

…

Giulio

Romano, Giants Room, Palazzo Te, Mantua, 1530-32.

Hence, immersive environments creating a fictitious or illusory ‘virtual’ space by projecting images onto the walls of a closed room have been investigated for quite a long time, though new technologies give a new impetus because of the ease of creation and of the « realism » of the constructed space. Another point, that we will develop much more deeply later is the interactivity introduced by the possibility of moving within the environment.

The

second type of apparatus is the HMD,

where the user/spectator is totally cut from the real world and immersed within

the fictitious space that in projected on two small monitors in front of the

eyes. This device became the allegorical emblem of virtual reality, the symbol

of high-tech art for the general public. The idea that the user/spectator is

immersed within himself is certainly

not alien to the success of this contemporary icon. Let us rewind the tape of

history and look back at the tradition of this concept.

Gotfried

Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716) is a key philosopher to understand contemporary

changes in our society. Not only is he credited for the invention of binary

notation[9]

and the birth of symbolic logic, which are both at the conceptual basis of

modern computers, but his baroque philosophy also prefigured many aspects

of post-modern ideas.

Gilles

Deleuze in his study on Leibniz[10]

considered that the closed room, without any windows, is the best visualization

of the Leibnizian concept of the monad

(cf. Monadology, 1714), and is to be

best exemplified in baroque art by the architectural design of the studiolo, for instance that of Francesco

I da Medici in the Palazzo Vecchio (Florence, 1570-72). A monad is an entity, a

soul « without doors nor windows » containing the whole world

‘folded’ within itself, representing “a subject as metaphysical point”, to use Deleuze’s

own words. In a similar manner the studiolo contains the whole world

(metaphorically) painted on its walls. Another philosopher used the concept of

the monad one century before Leibniz : Giordano Bruno (de triplici minimo et mensura, 1591). For Bruno, the metaphor

of the philosophical quest for knowledge is best expressed by the myth of Acteon (De gli eroici furori 1585) : Acteon, having seen Diana nude during

her bath, is chased by her dogs and made blind to punish him for having seen

such a beauty bound to secrecy. According to Bruno, the philosopher has also to

become blind and close his eyes to find the ultimate truth within himself, cut

out from the bodily sensations. A direct representation of those ideas can be

found in Ripa’s Iconologia, where

metaphysics is represented as a blindfolded allegory (here in Jean Baudoin’s

version of 1644). A similar picture is associated to the concept of ‘soul’ in

the work of the Czech humanist Comenius (Jan Amos Komensky) in his book Orbis sensualium pictus quadrilinguis (1658),

« the painting and nomenclature of all the main things in the world and

the main actions in life », i. e. a pictorial dictionary. Images are «the

icons of all visible things in the world, to which, by appropriate means one

could also reduce invisible things ». Soul is thus actually depicted as a

veiled head.

Cesare

Ripa, Iconologia (French edition by

Jean Beaudin, 1644)

Could

this be a plausible background, a cultural archetype, for the success of the

HMD imagery as the mean to dive into a virtual world within oneself ?

Moreover, does this HMD imagery suggest a deep melancholy, a sour regret, for

the loss of metaphysics in our modern world ?

III. The spectator’s point of view

An

important characteristic of virtual environments (VE) is the possibility for

the spectator to interactively move within such spaces, and perceive the

virtual world as through a subjective camera. In some sense the spectator

becomes an actor, although it can usually do little more than just wander

around[11].

This moving, first-person perspective is for some artists an answer to the

critic of modern perspectivism, mimesis

and “realism” of their works. An important point to note here is that we are changing from the cartographic

paradigm to the ichnographic paradigm[12].

The idea of the « cartographic eye in art » appeared recently to

reconsider modern art in the twentieth century[13].

This concept is especially relevant for the late and post-modernism in America

(Jasper Johns, Robert Morris, Robert Smithson). But with VE we are moving away

from the metaphor of the map to that of the path, from the third person point

of view (« God’s eye ») to the first-person point of view. As

Morpheus said to Neo in the blockbuster movie The matrix (1999),

« There is a difference between knowing the path and walking the

path ». We are thus leaving the Cartesian paradigm of an Euclidian,

homogeneous and objective space in which points could be described by a triple

of (x,y,z) coordinates for a new paradigm of a more subjective, and indeed

constructive space. This is indeed a return to the ideas of the French

mathematician Henri Poincaré (1854-1912), founder of modern topology, who

considered that a point in space should be described by the transformation that

has to be applied to reach it. Hence space is represented as a set of situated

actions. No one knows the totality of the map, no one can picture or order the

territory in any comprehensive way, even abstractly. The complexity of the

structure (“graph” to follow the word of Michel Serres, “rizhome” for Deleuze,

or “network” in the modern terminology) cannot be conceptually apprehended nor

depicted. It is worth noticing that, by moving from 2D to 3D, some information

is lost. First, because there is never a full blown representation (such as the

map). Second, 3D implies hidden surfaces, that is, a “part maudite” (Bataille), the devil’s part, which will always be

unknown. There is never light without shadows, nor life without death, as in

the Baroque world.

This paradigm

shift also appears in recent video artworks and best exemplified by artists

like Pipilotti Rist (in her videos, e.g. Pickelporno

1995, or installations such as Ever is

Over All, Venice Biennale 1997). Some works of Bill Viola also show the

same conceptual changes, for instance the Nantes’

triptych.

Another

area closer to VR that showed the same paradigm shift is 3D computer games[14].

The subjective camera also revolutionized the world of computer games a few

years ago with DOOM (PC CD-ROM, 1994). Although the game was incredibly simple

(hunt-and-kill) and the computer graphics quite poor, the immersive effect was

fully operational, even too much for some people. The user/spectator was

completely involved mentally, not to say physically, within the VE. However by

looking to recent developments, e.g. blockbuster games such as the Tomb Raider

series, one can only feel like a step back in the gaming industry away from

subjectivity : in TR, the player is behind a camera that follows the

heroin (cyberstar Lara Croft) as in a cartoon, he is not playing himself[15].

Similar third-person, TV-like cameras are also hardwired in systems such as

Sony’s Playstation or Nintendo 64 console [16].

Considering the history of movie films, one has to admit that the subjective

camera device, has been used very

scarcely since the 40’s, and was never well received by the general audience.

The most famous film of this genre being

Robert Montgomery’s Lady in the lake

(1947), and in fact the only one to have entered the cinema anthologies[17].

Let us hope that the use of the first-person point of view in VR artwork will

have a better fate, but we are maybe bound in today societies of the hegemonic

spectacle to what Jean Baudrillard

called more than thirty years ago[18]

the myth of the consumed vertigo ( « Mythe du vertige consommé »),

that is the lure of a second hand experience.

Nevertheless,

if a moving viewpoint might be richer than a classical one-point perspective

viewpoint, we should not forget the importance of simultaneous viewpoints or

privileged viewpoints. For Leibniz, if

there are multiple ways of perceiving reality « as the multiple

perspective views of a city », corresponding to different “truths”, there

is always a particular point of view which is better to understand the whole

thing. For instance in geometry, the

apex of the cone, from which all the conic curves are intelligible. This idea

of a specific viewpoint is also at work in

baroque perspective art such as the famous ceiling frescoes by Andrea

Pozzo in the Church of Sant’Ignazio in Roma (1691-94) which are to be seen from

a special point indeed inscribed in the floor of the Church. In other positions

the illusionist architecture depicted in the frescoes goes into incoherent

strands and seems close to fall down.

Some authors have proposed a detailed analysis showing why this

perceptually differs from classical perspective paintings on canvas[19].

But what is important here again is the presence of a precise point where

everything is in order and takes sense. This point where the illusion is

perfect might be the one where one understands the lure of representation and

maybe the fragility of reality. In contemporary art, artists rather use

simultaneous, fragmented, multiple viewpoints to show up the complexity of

their discourse. An immediate example of this is Joseph Kosuth’s well-known

work “one and three hammers” (1965),

showing a hammer, a photography of this

very hammer and a dictionnary definition of a hammer. The simultaneous

viewpoints on objects might be contradictory, to better ask the spectator about

the “reality” of the depicted object,

for instance in René Magritte’s “Ceci

n’est pas une pipe” (1926).

IV.

Interactivity, shared spaces and multi-user environments

Interactivity is indeed very limited in VE : in most of the so-called ‘interactive art’ only simple binary relations with objects (on/off) are usually implemented. That is, whenever the user moves to some point or touches an object, something happens. Recent new edia exhibitions have shown that the involvement of the spectator in interactive artworks is quite limited indeed, as his role is but to choose between a small number of possibility offered by the computer. There is only a limited and predefined dialogue between the spectator and the artwork. Could we have new modalities of interaction ? Could we go beyond (or below) the mediation of language or simple gestures ? Music or intuitive game-rules are simple examples of this, more complex device could be for instance to interestingly interact within artistic virtual worlds populated with artificial autonomous creatures. But a richer interaction would first require a real integration of the spectator in the artwork, which is not the case at present. In particular issues such as identity, self perception and the gaze of the Other are rather absent from VR works. There is a deep schizophrenia between the real and the virtual world, whatever the complexity of the technical devices (HMD, data-gloves, 3D sound) could ever be. We should nevertheless note that these questions are at the core of the contemporary reflection in art : let us only mention several video works of Gary Hill where the spectator is gazed at by the characters in the video movie and some works by Bill Viola, in particular slowly turning narrative, where the spectator is in some sense integrated into the artwork through a slowly turning mirror/screen, and refer more broadly to the omnipresent use of mirrors in paintings and/or installation art.

A new path to investigate for enlarging the degree of interactivity of new media artworks is the field of shared VE, where several users/spectators can enter the same digital space, for instance by the means of Internet connections, and therefore start an interaction between their ‘avatars’, i.e. their incarnations in the virtual world. This technology is currently used as an infrastructure for creating digital communities and meeting spaces where people basically do nothing else than chatting. This could be seen as a 3D version of the textual MUDs (Multi-User Domains) of the early nineties. Nothing prevents to use the same medium with a richer content in order to design complex interactions in artistic works. It possible to involve the spectator in a deeper way and to provide more complex experiences, such as including the user/spectator within the artwork itself. Indeed, virtual art spaces are fields of interactions, both between the artwork and viewers and between spectator themselves.

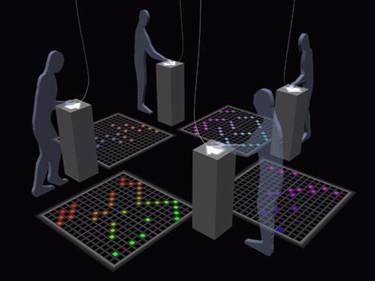

An

example of this, not in the domain of VR art but which could be a model for

many future works, is the installation “Resonance of 4” by the Japanese artist

Toshio Iwai (1994). It is composed of 4 computer booths, to be used

simultaneously by 4 spectators. Each person can produce some music, a simple

melody entered in the computer via a grid-like device. But the overall point of

this work is that spectators have to intuitively become aware that they are not

alone in the installation but have to initiate some musical dialogue and

co-operation to tune their melodies, whether in a consonant or dissonant way.

Therefore the real signification of this artwork is the dynamics that can be

created among spectators by using a simple interactive scheme such as music.

The core meaning of the artwork is thus an emergent behavior between the spectators. The artist has to create a playground and some adequate set of evolution rules in order to have this interaction to emerge. Meaning is thus not constructed by the artist and interpreted by the spectators, but fully and autonomously constructed by the spectators.

We

therefore have to find new models and new concepts for thinking this complexity

: self-organisation, emergent properties and autopoiesis, cf. the woks of the

late Francisco Varela[20].

Toshio

Iwai, Resonance of 4, 1994